Emerging Threats in the Cryptocurrency Ecosystem: Cryptocurrency Address Poisoning

By: Roger A. Hallman

1 Introduction

As blockchain-based cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin and Ethereum have gained popularity, criminal actors are constantly scheming new ways to steal assets from legitimate investors and users. Many of these schemes, such as ransomware and malware, are effective and well known, and therefore well studied by professional security researchers. However, criminals are innovative and always working to stay a step ahead of their targets. This blog post on cryptocurrency address poisoning is the first in a series on emerging threats to cryptocurrency users. These blog posts will have a different feel from recent entries, mainly due to the fact that these threats a fairly new and there is a dearth of information available; reputable sources may be limited to a few articles on popular websites because there is little refereed literature available.

Blockchains are decentralized ledgers where transactions are recorded across multiple independent nodes, and the cryptocurrencies that operate on those blockchains utilize cryptographic protocols (e.g., elliptic curve digital signatures, public key cryptography) to secure transactions and provide verifiable ownership of assets [8]. Every user on a blockchain has a public address which is derived from a public key value and which functions similarly to a bank account number. Transactions on a blockchain are public and immutable, thus maintaining public confidence in the ecosystem is essential to continued adoption.

Cryptocurrency addresses are typically alpha-numeric strings which are difficult to memorize or detect changes, and address poisoning is a relatively new attack which takes advantage of this fact. For example, Bitcoin addresses are strings which may be between 26 and 35 characters and Ethereum addresses are 42 characters. Users will often receive advice such as matching the first and last four characters of addresses. However, this means that users may miss subtle differences between an address that they intend to transact with and another address with the same leading and following characters. Cryptocurrency address poisoning attacks will target users and trick them into sending a transaction with an address which looks similar to an address which they have previously interacted with, assuming that the user will not detect the difference.

2 A Primer on Cryptocurrency Address Poisoning

Cryptocurrency addresses are long alphanumeric strings which are generated through hashing functions of public keys. A Bitcoin address may look like ”1A1zP1eP5QGefi2DMPTfTL5SLmv7DivfNa,” and a user may wish to send Bitcoin to this address. Address poisoning [11, 14] takes advantage of the similarity of the hypothetical Bitcoin address above and a different address ”1A1zP1eP5QGefi2DmRTfTL5SLmv7DivfNa.”

An address poisoning attacker generated the latter address to mimic the former, maintaining the leading and trailing characters, which is what most users check. The attacker will send the targeted victim small amounts of cryptocurrency over multiple transactions, an attack known as “dusting” transactions [4]. These dusting transactions may utilize established cryptocurrencies, or fake tokens (such as a token which impersonates well-known cryptocurrencies, e.g., a fake Tether) [13] which have no value. Many cryptocurrency wallets offer an auto-fill feature which keeps track of recent transactions, and the victim is likely to use this feature without verifying the full address to which they are sending funds. The attacker’s dusting transactions infiltrate the wallet’s history tracking, which gives the attacker’s mimicked address an appearance of legitimacy.

Cryptocurrency addresses are usually derived from public keys, which are in turn derivative of private keys. An address poisoning attacker can generate cryptocurrency addresses that look like a target by several methods. A fraudulent address may be generated by brute force, with the attacker generating a multitude of addresses until they find one that is similar to their target. Other tools, such as vanity address generators [5] allow an attacker to create addresses that mimic their target. After the attacker sends dust transactions to the victim, the poisoned address will appear in their wallet history. When the victim makes future transactions, there is a chance that they will select the poisoned address without verifying its legitimacy.

Unlike many attacks which are labor intensive for the cybercriminal, such as conducting reconnaissance operations to find exploitable bugs in software, address poisoning is a relatively low-cost and low-effort attack. The attacker’s most likely goal is financial gain by absconding with unsuspecting users’ cryptocurrency, which gives address poisoning attacks an excellent return on investment [9]. Other motivations may be political or ideological. Many businesses, political organizations, or non-profits accept cryptocurrency, and hacktivists may use address poisoning to impact the organization’s income stream. Or some attackers may simply want to sow distrust in an exchange, wallet, or even an entire blockchain network.

3 Case Studies of Address Poisoning Attacks

Address poisoning victims include both major and minor investors, law enforcement agencies, financial institutions, and even criminal networks. We will now explore several incidents of address poisoning to demonstrate how valuable cryptocurrency assets can be lost to this type of attack.

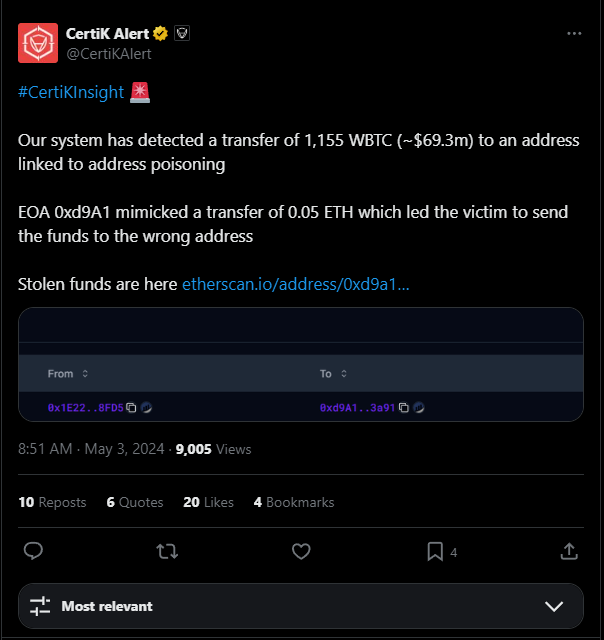

Figure 1: The blockchain security firm CertiK announced that a cryptocurrency whale was the victim of an address poisoning attack. [3]

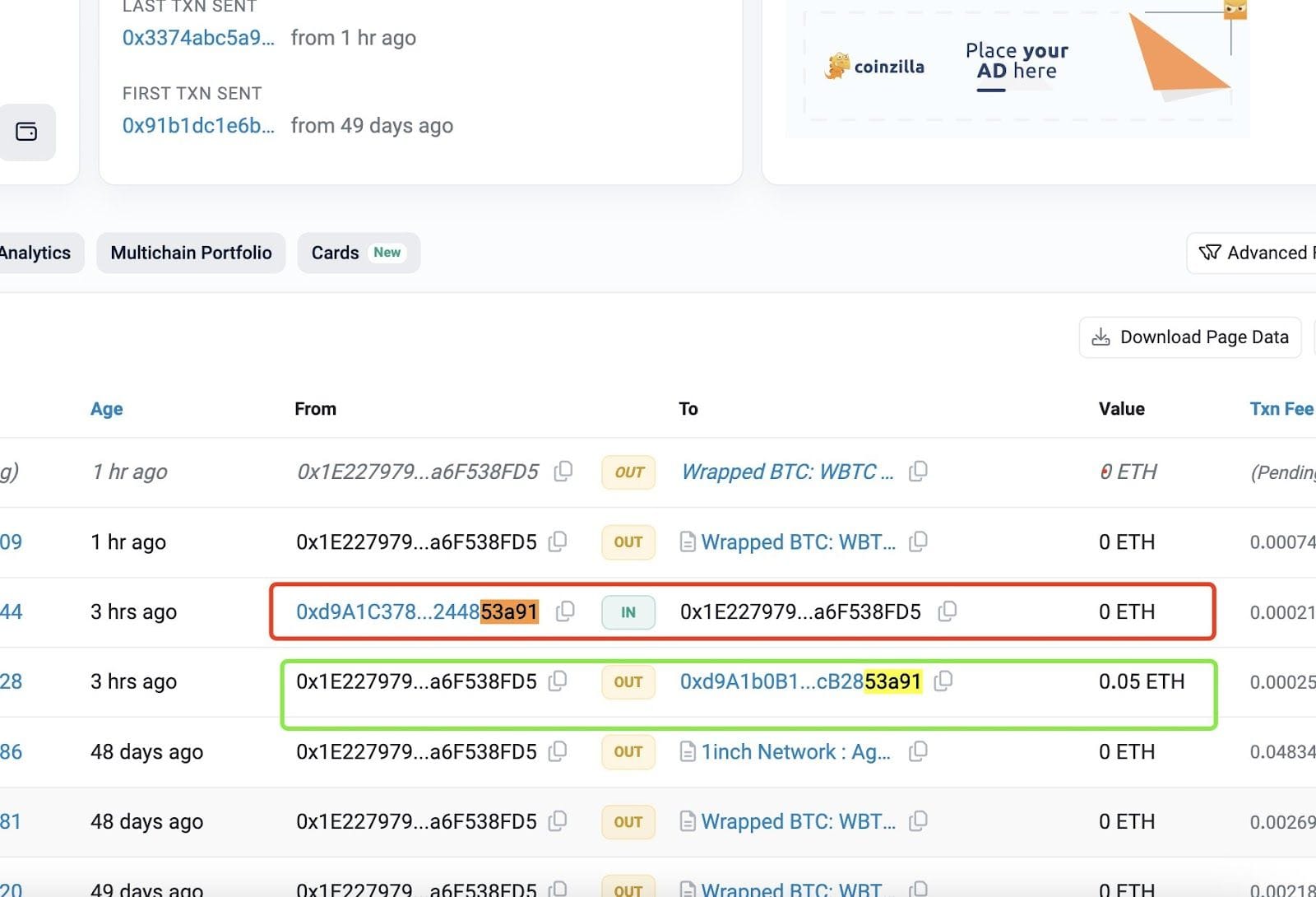

Figure 2: A blockchain tracker documents the victim’s legitimate and poisoned address transactions. The addresses outlined in green indicate a transaction from this account to a trusted address, while the addresses outlined in red are for a transaction from a phishing address to this account. [1]

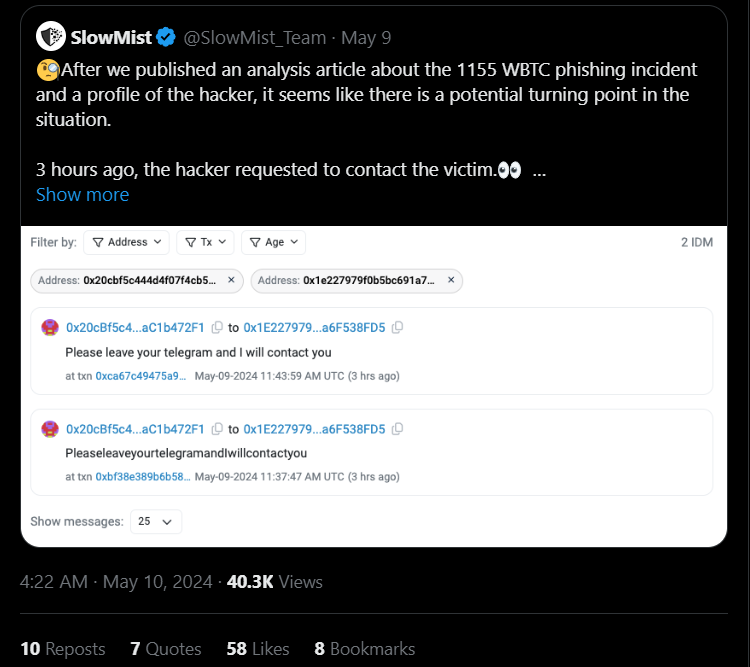

One notable case of address poisoning was reported in early May, 2024 (Figure 1) [1]. The blockchain security firm Certik reported [3] a poisoning attack where a major investor transferred 1,155 Wrapped Bitcoin (WBTC) valued at more than $69M. The attacker sent a small, malicious transaction which had a value of 0 ETH and a gas fee of approximately $0.65 to put their poisoned address in the victim’s transaction history, and only had to wait for the victim to copy and paste the address (Figure 2). The attacker swapped the 1,155 WBTC for 22,955 ETH, and distributed those funds to hundreds of other addresses. The victim sent the following message to the attacker through Ethereum’s Input Data Messaging System [10]: “You won bro. Keep 10% to yourself and get 90% back. Then we’ll forget about that. We both know that 7m will definetely make your life better, but 70m won’t let you sleep well.” After the victim made further attempts to communicate with them, the attacker began to send funds back to the victim (Figure 3) [12].

Figure 3: The victim and attacker negotiated a return of stolen cryptocurrency funds [12].

The Denver, Colorado FBI Office issued a warning in April, 2024 to warn cryptocurrency users to be wary of address poisoning attacks using token impersonation scams [6]. Their warning references an incident where a Colorado-based investor lost more than $2M to a stable coin investment scam, for which address poisoning and token impersonation were critical elements. The Denver FBI did not provide further information on this particular case.

The US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) fell victim to an address poisoning attack during the summer of 2023, losing more than $50,000 of cryptocurrency that had been seized as the result of a 3-year money laundering investigation [2]. The DEA had seized approximately $500,000 of Tether from Binance accounts which were allegedly used for laundering illegal narcotics proceeds. Those funds were sent to DEA-controlled hardware wallets and placed into a secure facility. A scammer was monitoring the Tether network and observed the DEA sending a small amount of Tether to the US Marshals Service, per standard forfeiture processing. The scammer promptly set up an address which closely resembled the US Marshals address, and airdropped the fake address into the DEA’s account which looked like the test payment made to the US Marshals. The US Marshals eventually noticed what had happened and alerted DEA personnel, who contacted Tether in an effort to freeze the fake account. However, the funds had already been converted to other cryptocurrencies and moved to new wallets. The agents reportedly only checked the following digits of the poisoned address, which demonstrates how many of these attacks can be easily avoided.

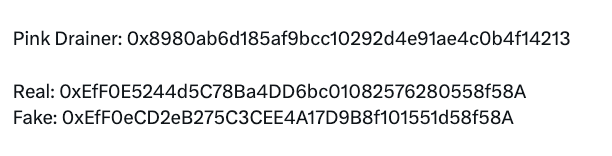

The cryptocurrency wallet-draining group Pink Drainer lost 10 ETH, valued at approximately $30,000, to an address poisoning attack in June, 2024 [7]. The attacker sent funds from an address which matched the leading 6 and following 6 digits of Pink Drainer’s previous wallet address (Figure 4). This attack came only a few months after Pink Drainer announced their retirement. Further information on the incident is not readily available.

Figure 4: The real and poisoned cryptocurrency addresses used in the attack on wallet draining group Pink Drainer [7].

4 Defending Against Address Poisoning Attacks

The case studies above demonstrate how easily users can be duped by address poisoning attacks, as well as how simple cryptocurrency hygiene can guard against becoming a victim [14]. Address poisoning attacks count on user laziness and preference for quick conveniences. Users always verify the full addresses that they wish to transact with and never rely solely on matching the leading or following address characters. Users should also pass on the convenience of copying and pasting or auto filling addresses from their transaction history, as these short cuts increase the risk of falling victim to an address poisoning scam.

While individual users practicing good cryptocurrency hygiene will limit exposure to address poisoning, there are important technical solutions which wallet developers and exchanges can institute to minimize the risks of users sending funds to poisoned addresses. Wallets and exchanges could give users the option to save verified addresses, which would reduce the need to copy and paste from transaction histories. Wallets can also warn users about detected dusting transactions, as well as give them the ability to sandbox or isolate dusted or impersonated tokens. Wallets and exchanges can interface with blockchain analytics and intelligence services to detect and block addresses known to be associated with address poisoning scams.

5 Conclusion

This blog article is the first in a series on emerging threats within the cryptocurrency ecosystem, and introduces the reader to address poisoning attacks. We covered the basic processes of the attack including the creation of poisoned addresses and dusting transactions, which scammers will use to get into wallet transaction histories. We surveyed several notable address poisoning attacks, and discussed mitigation strategies which can help cryptocurrency users minimize their risk of becoming the victim of one of these attacks.

Address poisoning is a subtle but effective attack that takes advantage of the inherent trust cryptocurrency users place in their transaction histories. Attackers sending small dust transactions and generating similar looking addresses, deceive users into sending cryptocurrency to malicious addresses, causing financial loss and eroding trust in the ecosystem. These attacks have resulted in millions of dollars worth of stolen cryptocurrency in the past couple of years, with victims ranging from investors, to law enforcement agencies, to other criminals. Users can reduce their risk of falling victim to an address poisoning attack by practicing good cryptocurrency hygiene (for instance, verifying the full address to which funds are being sent, rather than only checking the leading and following characters). However, the attack offers a favorable return on investment for the attacker, and so it is expected that address poisoning will remain a persistent threat as blockchain technology and cryptocurrency adoption continues.

References

[1] Behnke, R. Massive $68m address poisoning hack underscores ongoing cyber threat. Halborn (May 8, 2024). https://www.halborn.com/blog/post/massive-68-million-address-poisoning-hack-underscores-ongoing-cyber-threat.

[2] Brewster, T. The DEA accidentally sent 50, 000of seized cryptocurrency to a scammer. Forbes(August24, 2023). https://www.forbes.com/sites/thomasbrewster/2023/08/24/dea-accidentally-sends-50000-in-drug-proceeds-to-crypto-scammer/

[3] CertiK. Certik alerts tweet, May 3, 2024. https://x.com/CertiKAlert/status/1786378165050306774.

[4] Froehlich, M., Hulm, P., and Alt, F. Under pressure. a user-centered threat model for cryptocurrency owners. In Proceedings of the 2021 4th International Conference on Blockchain Technology and Applications (2021), pp. 39–50.

[5] Islam, M. M., Islam, M. K., and Hammoudeh, M. High-speed secure vanity address generator for user convenience in blockchain networks. In 2023 Fifth International Conference on Blockchain Computing and Applications (BCCA) (2023), IEEE, pp. 97–103.

[6] Migoya, V. Fbi warns of cryptocurrency token impersonation scam, April 26, 2024. https://www.fbi.gov/contact-us/field-offices/denver/news/fbi-warns-of-cryptocurrency-token-impersonation-scam.

[7] Mitchel Hill, T. Karma served: Pink drainer gets hit with address poisoning scam. Cointelegraph (July 8, 2024). https://cointelegraph.com/news/pink-drainer-hit-with-address-poisoning-scam.

[8] Narayanan, A. Bitcoin and cryptocurrency technologies: a comprehensive introduction. Princeton University Press, 2016.

[9] Nolasco Braaten, C., and Vaughn, M. S. Convenience theory of cryptocurrency crime: A content analysis of us federal court decisions. Deviant Behavior 42, 8 (2021), 958–978.

[10] Protos Staff. Refund of $70m ‘address poisoning’ scam ongoing, over 50% returned. Protos (May 10, 2024). https://protos.com/refund-of-70m-address-poisoning-scam-ongoing-over-50-returned/.

[11] Scharfman, J. Wallet drainers, crypto stealers and cryptojacking. In The Cryptocurrency and Digital Asset Fraud Casebook, Volume II: DeFi, NFTs, DAOs, Meme Coins, and Other Digital Asset Hacks. Springer, 2024, pp. 271–306.

[12] SlowMist. The attackers behind the 1155 $wbtc phishing incident appear to be returning the funds., May 10, 2024. https://x.com/SlowMistT eam/status/1788847044632920238.

[13] Xia, P., Wang, H., Gao, B., Su, W., Yu, Z., Luo, X., Zhang, C., Xiao, X., and Xu, G. Trade or trick? detecting and characterizing scam tokens on uniswap decentralized exchange. Proceedings of the ACM on Measurement and Analysis of Computing Systems 5, 3 (2021), 1–26.

[14] Zubic, E. How a few characters could cost you your crypto: The address poisoning threat. Medium (May 11, 2024). https://medium.com/coinmonks/how-a-few-characters-could-cost-you-your-crypto-the-address-poisoning-threat-97b62b9